Consumer Rights for Domestic & Sexual Violence Survivors Initiative

Newsletter on Coerced Debt – December 2023

Introduction

CSAJ’s Consumer Rights Newsletters share multi-level strategies by and for the field on critical consumer and economic issues that impact survivors’ safety. In this edition, we are featuring several resources, recent events/conferences and policy updates on coerced debt related to support for attorneys.

The Consumer Rights Newsletters are part of CSAJ’s Consumer Rights for Domestic and Sexual Violence Survivors Iniatitive, a national project that builds on the capacity of and builds partnerships between domestic violence and consumer (anti-poverty) lawyers and advocates.

What is Coerced Debt?

Coerced debt arises from situations where an abusive partner uses fraud or coercion to create debt in a partner’s name by taking out loans, using credit cards, or putting household bills in their partners’ name, among other types of debt. Coerced debt impacts survivor safety not only through the amount of debt they are saddled with, but by damaging their credit and thus restricting access to housing, employment, or other resources that rely on credit. It also compounds other financial hardships (e.g. when wages are garnished in debt collections) and can entangle survivors in lengthy, complicated, and costly legal cases, thus creating long term financial problems for survivors and limiting their options for safety. Check out the Coerced Debt Compendium here.

Family law and domestic violence lawyers and advocates, and their programs, play a critical role in increasing survivors’ access to civil legal justice and recourse for coerced debt,especially for low income, survivors of color and from other underserved or culturally specific communities.

In this edition of CSAJ’s Consumer Rights Newsletter, we share the latest in coerced debt research and advocacy to support your practice.

News and advocacy tips

NCLC Conference Presentation : Consumer rights advocacy for Domestic and Sexual Violence Survivors from Underserved Communities.

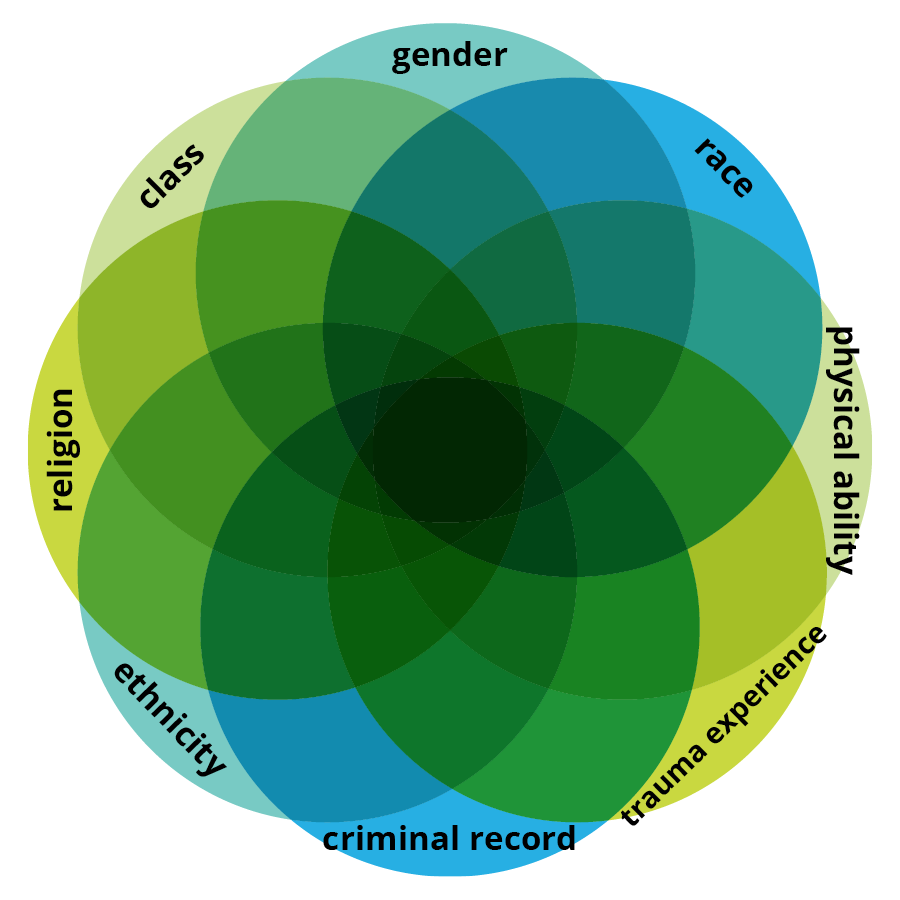

On October 27, Nkeiruka Aduba of CSAJ and Divya Subrahmanyam of CAMBA Legal Services presented at the National Consumer Law Conference in Chicago. This presentation focused on the economic ripple effect of domestic and sexual violence for survivors,and how survivors with marginalized identities are further negatively impacted when they navigate service systems. It discussed how advocacy strategies like survivor centered consumer advocacy, consumer rights and trauma informed approaches play a critical role in enhancing survivor economic safety. Advocacy practices discussed include screening, safety planning, building the case file, creating legal arguments, understanding available legal remedies (and gaps and limitations), as well as the importance of partnership with advocates and offering broad and creative advocacy to meet underserved survivors’ economic needs before, during, and after legal cases.

See the CSAJ NCLC Presentation 2023 for detailed tips and specific strategies. Key takeaways include:

First, build your foundations in economic abuse, coerced debt, and its unique and disproportionate impact on underserved survivors:

- Economic impact of domestic violence: Domestic violence is linked to a wide range of negative economic impacts including decreased safety options and increased risk of future violence. (slide 6&7)

- Economic abuse: Economic abuse involves “behaviors that control a person’s ability to acquire, use, and maintain economic resources, thus threatening their economic security and potential for self-sufficiency.” See Adams, Sullivan, Bybee, Greeson, Development of the Scale of Economic Abuse, 14(5) Violence Against Women Journal 563 (2008).

- The impact of domestic violence on underserved survivors:Survivors of all identities can experience economic abuse and consumer issues like coerced debt. However, survivors with marginalized identities may have unique experiences with consumer issues arising from DV like coerced debt and economic abuse and face additional barriers to addressing it due to intersecting systems of oppression including racism, sexism, classism, ableism, transphobia, and xenophobia. Domestic violence affects people of all races and ethnicities,BIPOC, persons from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, LGBTQIA+ individuals, people with disabilities, people that are incarcerated, elders,etc are disproportionately affected. For example BIPOC folks are more likely to experience domestic violence and less likely to receive the support and resources they need to heal and recover. This can significantly impact their mental health, leading to anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other mental health conditions.See CSAJ NCLC Presentation 2023

Then, build a practice of culturally sensitive and trauma-informed care to BIPOC and other underserved individuals to ensure all survivors can access justice and address the harms of economic abuse and coerced debt.

- Acknowledge the impact of systemic racism and discrimination, provide resources and support that are culturally relevant and appropriate, and create a safe and supportive environment that fosters healing and recovery.

- Make the case to your organization for why culturally relevant, survivor centered consumer advocacy matters: See the evidence in the PPT for positive outcomes survivors experience as well as benefits to staff.

- Help the survivor make decisions, including about what to share and how to proceed, based on their own goals, values, risks, and strengths as well as the advocate’s honest and transparent assessment of the circumstances.

- Be aware of your own power and how you use it e.g are we steering survivors toward a particular choice or action? Are we placing judgments or assumptions that reflect our own economic values? It is deeply important to create a no- judgment zone when working with survivors

- Build a trauma informed approach, including understanding what trauma is, the kinds of trauma or negative experiences that might affect a survivor dealing with a consumer issue and the ways this may manifest.

- Ask about money, economic needs, barriers, and challenges as part of safety planning. Listen for “red flags” or statements from survivors that may indicate economic abuse.

- Use techniques from Motivational Interviewing, or similar methods, to speak with survivors in ways that center their agency and supports self-determination. Techniques like: open-ended questions, curiosity (without judgment), reflective listening, and affirming experiences.For a detailed explanation of these issues see CSAJ NCLC Presentation 2023 ( slides 37-40)

Use the above foundations in all aspects and all stages of advocacy including: screening, safety planning, building the case file, and advocacy. Survivor-centered, trauma-informed, culturally relevant advocacy will help you ensure underserved survivors have access to powerful civil legal remedies and can develop creative approaches to ensure legal and non-legal outcomes support their long term economic security. See slides 25- 67 CSAJ NCLC Presentation 2023 for specific tips.

VAWA’s New Economic Abuse Language: How Can We Use it To Expand Economic Justice for Survivors?

On November 8th, CSAJ held our first-ever Consumer Rights Legal Roundtable, featuring several speakers coming together to discuss the economic abuse provision language included in the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization of 2022 (34 USC 12291). We explored how attorneys, advocates, and programs can leverage this groundbreaking provision to expand economic and consumer justice for survivors, particularly for underserved and marginalized communities.

‘‘The term ‘economic abuse’, in the context of domestic violence, dating violence, and abuse in later life, means behavior that is coercive, deceptive, or unreasonably controls or restrains a person’s ability to acquire, use, or maintain economic resources to which they are entitled, including using coercion, fraud, or manipulation to—

(A) restrict a person’s access to money, assets, credit, or financial information; (B) unfairly use a person’s personal economic resources, including money, assets, and credit, for one’s own advantage; or

(C) exert undue influence over a person’s financial and economic behavior or decisions, including forcing default on joint or other financial obligations, exploiting powers of attorney, guardianship, or conservatorship, or failing or neglecting to act in the best interests of a person to whom one has a fiduciary duty.’’ 34 USC 12291

Nearly all survivors experience economic abuse, yet it is a deeply under addressed issue that threatens survivors’ safety not only in the short-term but throughout their lives. Providing the best support for survivors often necessitates DV attorneys and consumer law attorneys working together to gain a full picture of a survivor’s life and address their holistic economic needs. Many experience and are saddled with coerced debt – or debt created through fraud (identity theft), coercion, or manipulation. While more states are adopting greater consumer protections to address this harm, allowing survivors to dispute, block, or remove coerced debts from credit reports, legal protections and remedies remain limited. Roundtable participants shared how other forms of economic abuse, as well as factors associated with living in poverty, compound the lasting and negative effect of coerced debt. For example, survivors are often forced to give up salaries, trapped in rent arrears or public benefit debt, or experience the psychological threat of knowing an abusive partner has their identification information or documents to use against them at any time. Incarcerated survivors often have little recourse to debt incurred in their name during incarceration.

In this landscape of limited consumer protections and legal remedies, the new VAWA language offers advocates and attorneys new possibilities and opportunities.

Here are some of the ways Roundtable participants shared that they are using the new VAWA language:

- Offers language to substantiate legal arguments to address economic abuse in family court, including:

- adding economic crimes to protective order filings,

- getting identity documents returned to survivors,

- leveraging for larger portions of retirement accounts, longer duration of alimony, or shift liability of coerced debt to the abusive partner/spouse,

- citing the definition in VAWA to beef up arguments in identity theft / unauthorized use dispute letters and to help explain why “familial fraud” can still be identity theft. (banks / credit card companies often deny claims when it is a spouse or household member who commits identity theft.)

- Use it as model language in states whose definitions of domestic violence are limited and do not include economic abuse:

- Whatever law does exist, use the provision as a persuasive authority, especially in family law cases where judges may have a broader discretion.

- See and use definitions/laws in other states as well. Some have included economic abuse and coerced debt.

- Unpack the language in your program, community, and with partners to describe what “economic abuse” looks like for survivors you work with in real life:

- Look at the words, ideas in the provision to unpack in community, bring together all resources and service providers to build capacity around potential solutions.

- Mapping the Economic Ripple Effect of Violence in your community is one activity that may help.

- Help build capacity around identifying and addressing economic abuse and coerced debt among marginalized communities. For example, with immigrant survivors:

- Immigration attorneys working within immigration law see economic abuse in all kinds of ways (e.g. no access to documents, social security number usage). They have been creative in the past so this language helps to cement what’s been done for many years.

- Can help avoid bringing attention to their legal status, while paying attention to unique barriers to accessing economic resources (like public benefits for mixed status families).

- Building more documentation in our own work – learn what strategies people are rejecting as well. A lot of immigrant survivors seek alternative ways for relief.

- Trying to enforce your rights, especially in engaging with LE can have unintended consequences – i.e garnished wages from any family member

- New language allows for protections for self-attestation to being trafficked

- Support advocacy efforts to educate judges, courts, law enforcement, and other systems:

- Helps judges focus not on a ‘spotty work history,’ but why it’s “spotty” – helps explain and give evidence to the role of economic abuse. Attorneys can build this type of documentation into their own work too.

- Police reports are often required to address identity theft. The VAWA language can be used to educate police chiefs/departments on identity theft when the perpetrator is not a stranger, and lower barriers to reporting that survivors may face. And to remind them that the goal is not necessarily for law enforcement to find the perpetrator of identity theft (in the case of domestic violence, the partner or ex-husband), but so survivors have documentation to address it in their family law cases or via consumer legal remedies.

Essential resources that were shared and discussed:

- CSAJ’s Compendium on Coerced Debt – a critical resource on the legal and non-legal state of coerced debt advocacy

- Information for survivors looking to change their Social Security Number

- CSAJ has a robust Resource Library on a range of consumer issues impacting survivors’ safety. Search for taxes, credit repair, and beyond for past webinars, resources, and beyond

- Coerced Debt State Tracker – documents and tracks state coerced debt protections and laws to support legal advocacy with survivors

Addressing Coerced Debt in Divorce: Study Findings & Implications for Attorneys & Advocates

On November 16th, CSAJ invited researchers, Adrienne Adams, Angie Kennedy, and Angela Littwin to share and discuss findings from their recent research: the first in-depth study of coerced debt among 188 divorcing women in Texas. Funded by the National Science Foundation, the study examined how coerced debt operates in abusive marriages and the effectiveness of legal remedies available in divorce and debtor-creditor law. One-third (31%) of participants were Women of Color, 90% had at least some college or higher education, and while 69% had household incomes above the median for the area, 80% of women’s personal income was below the median. This sample had maximum privilege in finding recourse for coerced debt, and yet the study revealed the legal remedies through divorce law and debtor-creditor law (unauthorized use, bankruptcy, and statute of limitations) were largely ineffective.

Family law and domestic violence lawyers and advocates, and their programs, play a critical role in increasing survivors’ access to civil legal justice and recourse for coerced debt. Especially for low income, survivors of color and from other underserved or culturally specific communities.

Key findings:

- 80% experienced economic abuse and 67% had coerced debt.

- On average, women with coerced debt had 4-5 different accounts with coerced debt. The median amount of coerced debt a woman had was $23,248. The amount of coerced debt held by all women was $13,689,029.

- The most common types of coerced debts were credit cards, student loans, vehicle loans, personal loans, and mortgages. There was coerced debt on nearly half (47%) of all credit card accounts, and on about 10% of the other types of accounts.

- Excluding home and property loans, accounts with the highest amounts of coerced debt were credit card, vehicle, student loans, personal loans, and unpaid taxes.

- Women with coerced debt had significantly lower estimated credit scores (average: 676) than women without coerced debt (average: 706). And the majority of participants’ credit scores would improve if coerced debts were removed. For one-third of participants (32%), their credit scores would improve by over 20 points, which is enough to change the interest rate one would get on a mortgage.

- Women of Color had more coerced debt (80% vs 63%), held slightly higher amounts ($24,565), were more likely to have personal loans (19% vs 9%), would benefit more from deleted coerced debt from their credit scores, and were less likely to be able to pay off coerced debt by the time of divorce (70% vs 54%) than White women. Women with lower incomes were also significantly less likely to be able to pay off coerced debt by the time of divorce, compared to those with higher incomes (64% vs 43%).

- Only 1 participant received money in the divorce specifically for the purpose of paying coerced debt. The overwhelming majority of participants (83%) had no coerced debt shifted to the ex-husband in divorce. And most did not receive enough assets in the divorce to pay off their coerced debts.

- Some of the coerced debt could be relieved under available debtor creditor law, but awareness and willingness to use them were mixed.

- Bankruptcy would relieve the most coerced debt (75% of accounts could be discharged) and nearly all knew it was an option, but said it was the least acceptable remedy.

- Unauthorized Use was the most acceptable remedy to participants (66% said they use it), and 55% of accounts could be relieved under it. But willingness to use it declined to 38% when the requirement of a police report was mentioned.

- Only 4% of accounts could be relieved under Texas Statute of Limitations, and few knew about it (14%), though most participants were willing to stop paying on their debts to get it.

Luna, a 27 year old Middle Eastern participant with a college degree, when asked if she had any priorities going into the divorce:

“To be honest, not really. I didn’t have any specific things I wanted to be on there. He did…he had his terms… Honestly, I was really terrified of what kind of revenge he was going to take out on me. So I was going to be compliant either way. So I was like, best case scenario is that he just decides that we’re going to halve everything. And I get lucky [if] he decides that.”

How advocates, attorneys & programs can use findings:

- Use the findings on common types and amounts of debt, and differences by race and income to inform your assessment, issue-spotting, and advocacy practices. Advocates can find additional guides and tools for starting the economic conversation and addressing coerced debt, including credit repair, in our ACCESS to Justice eCourse. Attorneys can find additional screening and legal advocacy strategies in our Compendium on Coerced Debt

- More work is needed to ensure low income survivors from culturally specific and underserved communities have access to and recourse in family and consumer legal justice to address coerced debt. Contact CSAJ to join a future Consumer Rights Legal Roundtable to build creative, holistic, and culturally relevant legal strategies. And use this resource to understand the unique manifestations of coerced debt among survivors from marginalized communities.

- Judges, court mediators, and attorneys played important roles in whether coerced debt was identified or addressed (equitably distributed) in divorce cases. Use the key findings above, along with data from your own cases to educate family law judges and court actors. You can also use findings to build partnerships with local banks or credit unions who can offer financial and credit-building services to low-income survivors impacted by coerced debt.

- Willingness to use Unauthorized Use law declined to 38% when filing a police report was required. Use the findings to set up meetings or trainings with police departments to discuss what identity theft from an intimate partner looks like, and how they can lower barriers for survivors to report identity theft committed by an intimate partner. Remember: In jurisdictions where police reports are required, the goal is not necessarily for law enforcement to find the perpetrator of identity theft (in the case of domestic violence, the partner or ex-husband), but so survivors have documentation to address it in their family law cases or via consumer legal remedies.

- States are continuing to expand protections and more viable remedies for coerced debt. Explore your state laws and view this coerced debt legislation tracker to learn from other state laws to inform litigation strategies.

Policy Spotlight

CSAJ hosts a National Coerced Debt Working Group that comprises over two dozen attorneys, advocates, researchers and policy makers who bring diverse expertise and practice to advance systems and policy change to address coerced debt. On September 13, 2023, the group met and each of the subcommittees presented the following developments:

Emerging Issues:

- Adrienne Adams and Angela Littwin shared initial findings from the first-ever study on coerced debt among divorcing women. A detailed coerced debt assessment tool and series of policy brief are in development.

State Policy:

- DC – Advocates in DC conducted a meeting with Phil Mendelson, Chair of the DC Council, and Legislative person, Blaine Stum. There is work being done on a brief to share with council members. The group requested materials to educate lawmakers on Coerced Debt.

- NYC – Advocates in NYC are responding to a memo they received from a debt collector lobbying group. Legislative update: The NY State Bill did not pass in the last session, and advocates will begin advocacy again during this session.

- View the CDWG’s Coerced Debt State Policy Tracker for details on various state legal protections and remedies available for coerced debt, and add your state’s developments.

Model Policy:

- Carla Sanchez-Adams and Andrea Bopp Stark have drafted a Model Coerced Debt Policy. The working group is providing feedback, and the Model Policy will be distributed early 2024.

National Clearinghouse:

- The National Coerced Debt Clearinghouse, under development, will share information, research and governing law for advances to advance coerced debt advocacy. You can view CSAJ’s Coerced Debt Resource Digest, in the meantime.

CSAJ Resources

Coerced Debt Resources

- August Newsletter – has definition of coerced debt, tools for advocacy, links to compendium

- Coerced Debt Compendium – 4 part guidebook on coerced debt, understanding the issues, holistic advocacy approaches to addressing survivors needs, and legal strategies to addressing coerced debt. Also see:

- Understanding Coerced Debt

- Legal Strategies to Address Coerced Debt

- Coerced Debt Defense and Safety for Survivors – Multi part webinar about assessing and gauging impact of coerced debt as well as legal and non legal strategies to address coerced debt with survivors

- Debt in the context of Safety – Video webinar discussing how coerced debt can manifest in survivors’ lives

- NYC Survivor Economic Equity Policy Platform: Coerced Debt Issue brief – features very in depth coerced debt systems map

- NYC SEE Coerced Debt Issue brief – features very in depth coerced debt systems map

- Guidebook on Consumer and economic Civil Legal advocacy for Survivors – Less relevant but still a useful resource with some information on coerced debt

- Texas Appleseed Coerced Debt Toolkit – geared towards survivors

- Coerced Debt: The role of Consumer Credit in Domestic Violence – Research article by Angie Littwin

- Think About It: Reviewing the survivor’s credit report is an important part of coerced debt advocacy. Be aware that current information appears on a credit report and could put a survivor who is being stalked in greater danger. See CSAJ’s Guidebook Chapter on Credit Reporting & Repair.

- Coerced Debt Resource Digest that contains additional resource links, published articles, toolkits, and a list of relevant CSAJ trainings about coerced debt.

This project is supported all or in part by Grant No. 15JOVW-22-GK-04011-MUMU awarded by the Office on Violence Against Women, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in the publication/program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of Justice, Office on Violence Against Women.