July 13, 2016

Reflections from CSAJ’s Founder and Executive Director, Erika Sussman, on police violence against people of color and the implications for the violence against women movement.

ur country is reeling from the violence that we have witnessed this past week. Two African American men were killed violently by police officers. Alton Sterling lay pinned to the ground, executed by multiple gunshots. Philando Castile, pulled over for a broken taillight, was killed while still inside of his car in front of his girlfriend and her four-year old child. I repeat: four-year-old child. These are not discrete incidents. Rather, these events come after a long litany– and much longer, though often less visible, history– of killings by police officers against Black men, women and children across our nation.

We who advocate for survivors of domestic and sexual violence are called to ask ourselves: How do these and other acts of police violence impact survivors, particularly survivors of color? And, how must the reality of violence against communities of color inform our advocacy on behalf of survivors?

The violence against women movement’s reliance on criminal justice interventions has exposed survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault to increased danger. A series of strategic, political, and at times conciliatory, decisions have resulted in formal domestic violence interventions that are primarily couched within a criminal justice system response. In the 1970s, when advocates for battered women sought to address the harm of domestic violence, they pursued criminal justice remedies, in part to ensure public recognition of these crimes against women. Advocates of color warned that criminal justice interventions would lead to unintended consequences. They knew that slavery, Jim Crow segregation and racism had created deep and legitimate mistrust within many communities of color towards the police, and that those impacts were not merely historical but translated into current day biases, which posed acute risks to survivors and their communities.

Nonetheless, over the objections of advocates of color, mainstream, white domestic violence agencies clamored for criminal justice interventions.

States moved to recognize domestic violence as a crime, which could be enforced by police and prosecuted in the criminal courts. And later, advocates pushed for mandatory arrest and prosecution policies, in an attempt to minimize discretion and shift domestic violence from a private matter to a state matter that required accountability, regardless of a victim’s wishes or coerced pressure by her abusive partner. In the early 1990’s, after continued critique of states’ handling of domestic violence, advocates agitated for federal legislation targeting gender-based violence, which resulted in passage of the Violence Against Women Act, implemented by the Department of Justice, the federal law enforcement agency.

And, while the push for criminal interventions have dramatically enhanced the legal attention given to domestic violence, the consequences predicted by communities of color have come to bear in devastating ways. An incident of domestic violence ushers in a police response that can have violent, and sometimes lethal, consequences for survivors and their partners. It is frighteningly common for police, unable to distinguish between perpetrator and victim, to conduct a dual arrest, which in turn leads to a series of damaging collateral consequences for survivors in countless areas of their lives (from losing their job to losing of custody of their children). And indeed, domestic violence survivors of color, and immigrant survivors, have to engage in complex decision-making related to law enforcement involvement: protect their community from police intervention but risk their own safety at the hands of their abusive partner, or seek state protection but risk further discrimination, community isolation and violence by the state itself against their partners, their children, their communities, themselves.

Once police are called, survivors and their children are exposed to greater scrutiny and an increased risk of violence by other state actors. For example, a 1999 case in New York City revealed a child protection agency’s policy of presumptively removing children from mothers who were victims of abuse (Nicholson v Williams). In that case, ninety-five percent of instances of child removal were experienced by women of color who were living in poverty. And, as the Sandra Bland and Holtzclaw cases have demonstrated this past year, women of color experience greater risk of targeted physical and sexual violence by police officers themselves. As one survivor in the Holtzclaw case exclaimed, “What kind of police do you call the police on?”

All of the above begs the question: Is the criminal justice system the answer? Put differently:

Given the historical and present day reality of police violence against people of color, how can we, as an anti-violence movement, possibly rely upon the criminal justice system as the primary source of protection for survivors of color?

I think the simple answer is: We cannot.

First, the criminal justice system is not a reliable source of protection. Often state actors commit violence against survivors of color that is worse than that which they have experienced at the hands of their abusers. Surely, in the world that we aspire to, survivors regardless of skin color would be able to reach out to police for protection. But, unfortunately, that is not reality, and survivors of intimate partner violence cannot afford to live in an aspirational world– not when their lives literally depend upon it.

Second, criminal justice remedies do not provide the resources that survivors say they need. In a study conducted by Cris Sullivan many years ago, when asked to articulate their needs, African-American survivors of domestic violence named access to material resources (income, housing, childcare, transportation) as their top priority. Data suggests that, for all survivors, regardless of race, access to income is the greatest predictor of long-term physical safety. Are our current responses attuned to these needs, as defined by survivors?

At the same time, there is a reciprocal relationship between violence and poverty. Violence leads to economic hardship, and economic hardship, in turn, exposes survivors of intimate partner violence to increased risk of violence. Such economic impacts are not incident-based, rather the economic impact of violence ripples throughout the life course, leaving survivors with profound long-term economic harms (that negatively impact their health and access to employment and vulnerability to future violence).

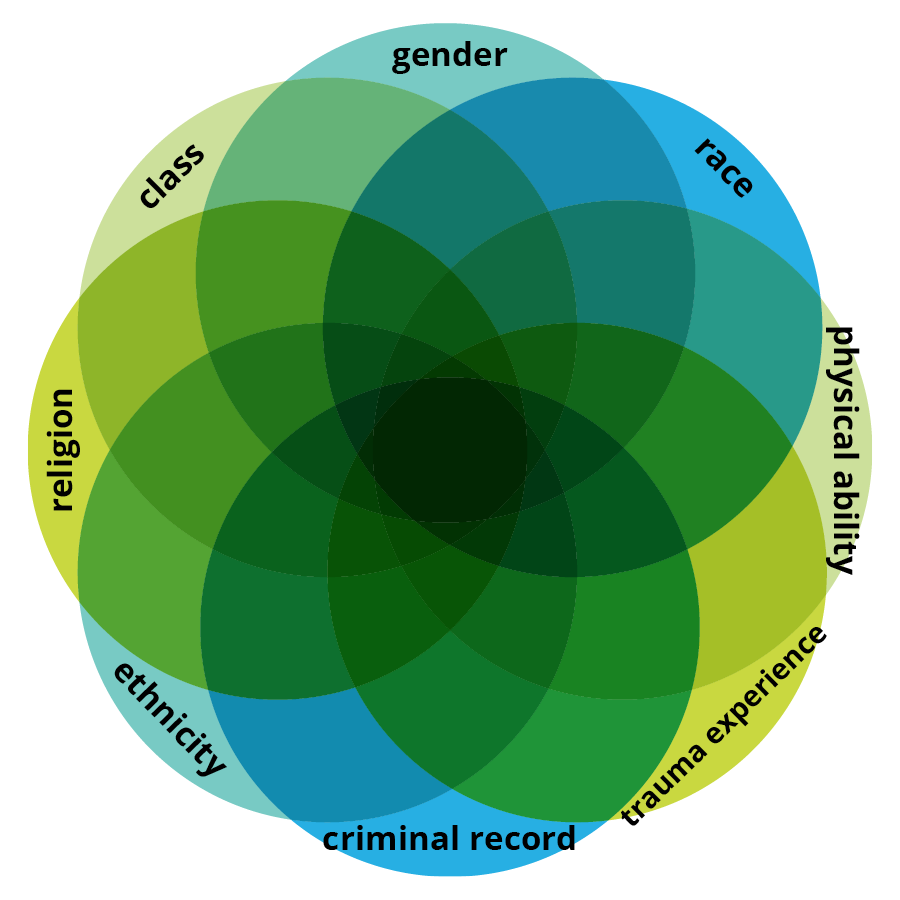

And, while the impact of economic abuse is well documented, much less is known about the systemic economic barriers facing survivors. Women of color experience domestic violence and sexual assault at much higher rates than their white counterparts. People of color live in poverty at a rate greatly disproportionate to whites. Some of these barriers are “place based,” meaning they result from “poor opportunity structure” (lack of access to services, material resources, transportation, employment opportunities, and concentrated poverty), while others are race based, taking the form of differential treatment by law enforcement, prosecutors, teachers, public benefits workers and are often driven by implicit racial biases as well as policies, protocols, and remedies that have a disparate impact on people of color.

What does safety for survivors really require? Given the inadequacies and risks associated with the criminal justice response, along with the clear links between poverty, race, and violence, advocates must refocus our energy on interventions that prioritize economic and racial justice.

Consumer and economic civil legal remedies offer tools for addressing profound harms resulting from violence, such as debt, credit damage, foreclosure, tax liability, and related barriers to employment. In a 2012 survey, CSAJ found that few programs and practitioners had institutionalized mechanisms for addressing the economic needs of survivors. A handful of groundbreaking sites across the nation have engaged in participatory action research with survivors and strategic planning with programs and coalitions to craft partnerships and provide the infrastructure needed to address the economic needs of survivors.

Only by centering the barriers facing survivors of color can we identify the systemic inequalities that impede their paths to economic and physical safety. What are the concrete economic structural barriers facing survivors of color? What strategies are needed to remove those barriers to create the economic opportunity needed for safety? Partnerships between anti-violence, anti-poverty, and race equity advocates are critical. CSAJ’s Race and Economic Equity of Survivors Project is drawing upon the narratives of survivors and their advocates along with the quantitative methods (including community mapping) and legal strategies of race equity advocates to better describe and advocate for impactful systems change.

If there was ever a question before, the criminal justice system is not the answer– not now, and maybe never.